London’s burning, London’s burning

Fetch the engines, fetch the engines…

This September marks 358 years since The Great Fire of London changed the landscape of London and gave us the city we know and love today.

.jpg)

Image: One of the many reminders you can find around East London to commemorate the Great Fire

Between 2nd and 6th September 1666, a huge inferno raged around The City of London, stretching for several miles and destroying thousands of buildings, including iconic places like St Paul’s Cathedral.

The Great Fire of London began at Thomas Farriner’s Bakery on Pudding Lane, a small street in the City of London. The street got its name because of the offal (or pudding) that was taken down to the river to the waste barges from the butchers at Eastcheap Market. It was also one of the world’s first one-way streets, having been so since 1617. The bakery stood 202 feet from the site of the Monument to the Great Fire of London on the east side of Pudding Lane, it was paved over in 1886 when the modern Monument Street was built, but you can still see where the bakery was thanks to a plaque placed by the Bakers’ Company in 1986.

.jpg)

Image: The road sign at Pudiing Lane

Let’s break down what happened, the main players of the fire and the impact it had in the months and years that followed.

London in 1660s

By the time of the Great Fire, London was the largest city in Britain and the third largest in the Western world. The actual City of London hasn’t changed much since those days, like modern times, the City of London was the commercial heart of the capital and had the largest market and busiest port in the whole of England. It pretty much remained as it had since the Romans created the settlement of Londinium, with life becoming incredibly crowded within the walls and several smaller settlements springing up on the outside of the walls, allowing it to stretch West towards the Strand and the Royal Palace and Abbey at Westminster and across the River Thames into Southwark.

The year before the Fire was known as the Year of the Plague following an outbreak of the bubonic plague which killed 1/6th of the population. This was exacerbated by the living conditions of the time, the City in particular was full of traffic and was heavily polluted. The City featured an overcrowded warren of narrow, winding streets with many of the dwellings being constructed as multi-storey timbered tenement houses, some with jetties (projecting upper floors or windows) to create extra living space. These were built using wood and thatched rooves, despite both of these things being outlawed by King Charles II. It was, however, cheap to create housing in this way and despite his threats to imprison builders and to demolish dangerous homes, the City Governors were reluctant to follow through. The City and the Crown had a tense relationship, this area of London had been a stronghold for parliamentarians during the English Civil War and uprisings against the crown continued here well after the restoration. The only areas of The City that used stone or brick was the very centre, where the merchants had spacious and well built manors and further out, towards places like St Paul’s Cathedral.

Prior to the Great Fire of London, there had been a number of major fires in the area, the last one taking place in 1633. It is also important to note that at the time of the Fire, England was at war with both France and the Netherlands, known as the second Anglo-Dutch War.

Important figures during the Fire

King Charles II and James, Duke of York

The Royal brothers took charge and thanks to their efforts, the fire didn’t spread as far as it could have done. This combined with a drop in the wind helped stop the spread.

Thomas Farriner

English Baker and Church Warden, his bakery in Pudding Lane was the starting point for the Great Fire of London. He joined the Baker’s Company in 1637 and had his own shop by 1649. He was a well known baker in the city and provided bread to the Royal Navy during the Anglo Dutch War.

He, his family and some domestic servants lived above the bakery. After the fire, he rebuilt the business on Pudding Lane.

Sir Thomas Bloodworth

The Lord Mayor of the City of London. He was in charge of the area impacted by the fire and many say that his ineffective leadership caused much of the damage. He was given the job because he was seen to be a bit of a “yes man” however, he often crumbled under pressure and didn’t possess any actual skills for the job. When the fire broke out, he was annoyed at being disturbed and went off back to bed without giving any instructions to the firefighters.

On the second day of the fire, he fled the city and the King took over the managing of the fire.

Samuel Pepys

The famous diarist made many of the accounts of the fire. He also delivered messages from the King to the Lord Mayor.

Robert Hubert

Robert was a French watchmaker who was known to have mental health problems and limited mobility. He confessed to starting the fire, despite many not believing him, a scapegoat was needed, so he was charged and sentenced to death. The Farriner family were among those who signed the bill for his execution.

Following his execution, it was discovered that he was on a boat in the North Sea when the fire actually broke out.

The Timeline

Sunday, 2nd September 1666

The fire broke out in Thomas Farriner’s bakery on Pudding Lane in the early hours of the morning. The family were trapped in the house upstairs, but escaped through an upstairs window, except the family’s maid, who was too scared to jump to the street, she was the first casualty of the fire.

The Farriners sounded the alarm and the residents of the neighbouring buildings rushed to help put out the fire, after an hour, the Parish Constables were on the scene and judged that they would need to demolish the neighbouring properties to stop the fire, something that was common in firefighting at the time, but in order to do this, they would need the permission of Lord Mayor Thomas Bloodworth.

By the time Bloodworth arrived on the scene, the adjoining houses were on fire and the flames were heading towards the waterfront, where several warehouses stored flammable items. Bloodworth refused to begin demolishing buildings as he stated that permission would need to be sought from the building’s owners rather than the tenants, so a decision couldn’t be made. So, he headed back to bed.

At a more reasonable time in the morning, diarist, Samuel Pepys, ascended the Tower of London to view the fire from the battlements. He wrote in his diary that from what he could see, around 300 houses had been destroyed. By that time, the fire had reached the river and the houses along London Bridge were burning.

Pepys boarded a boat and travelled around the area, he managed to catch a glimpse of Pudding Lane and noted that several people were trying to save their possessions, either by throwing them in the river or by moving them to St Paul’s Cathedral. He then continued on down to Whitehall, where he spoke to the King and the Duke of York. Charles commanded him to tell the Lord Mayor to begin demolition and James, Duke of York, offered the use of the Royal Life Guards

By mid-morning, many had abandoned the attempts at extinguishing the fire and had tried to flee. Unfortunately, the crowded nature of the streets and the general panic made it difficult for firefighters to get where they needed to and the City gates became bottlenecked. Pepys reached the Lord Mayor, who refused the offer of more soldiers. Around this time, Charles II sailed down from Whitehall and saw that the houses were not being demolished, he overrode Bloodworth’s authority and ordered demolitions west of the fire zone.

By the afternoon, the weather had become windy, fuelling the flames. By now, the fire had become a huge firestorm and had travelled 500 metres west from its starting point.

Monday, 3rd September 1666

At daybreak on Monday, the fire had begun to spread west and north. It had also made its way across London Bridge towards Southwark.

By the afternoon, it had reached the banking district on Lombard Street in the heart of the City – reports from the time commented on the bankers trying to save their gold coins before they melted. At this point, hope was seemingly lost as there was little effort made to save the wealthy and fashionable districts in the City. The Royal Exchange caught fire in the late afternoon and was a shell within a few hours.

On Monday, rumours started spreading that the fire wasn’t an accident and was actually an act of warfare thanks to England’s involvement in the Anglo Dutch War. Many believed that an invasion was imminent and that the fire had been started by undercover agents. From this there was a wave of street violence against foreign-born people, particularly the French, the Dutch and the Catholics. This gained momentum when the General Letter Office on Threadneedle Street, through which post was sent out across the whole country, burned down. The London Gazette managed to get out their Monday edition before their offices too, were caught up in the fire. Widespread rioting began, causing the Coldstream Guards and the Trained Bands to abandon fire fighting to restore order.

By the afternoon, Bloodworth had left the City and King Charles II took charge. He put his brother, the Duke of York in command and several command posts were set up on the perimeter, manned by a trusted member of court and each given the authority to order demolitions where needed. James and his Life Guards rode around the streets, rescuing people and attempting to keep order. That evening, Baynard’s Castle in Blackfriars, a large stone building, which was seen as the western counterpart of the Tower of London, caught fire. It was completely destroyed and burned through the night.

Tuesday, 4th September 1666

Tuesday is deemed to be the biggest day of destruction since the fire broke out.

On Tuesday morning, the flames had made it to Temple Bar, where the Strand meets Fleet Street. The command post there was supposed to stop the fire’s advance towards Whitehall, but assumed that the River Fleet would form a natural firebreak. However, the strong easterly wind caused the flames to jump the river.

By midday, the fire had breached Cheapside where several luxury shopping outlets were located. The Duke of York and his men created a huge firebreak here, which although was breached at multiple points, did slow down the spread. Through the day, the flames began to move closer to the Tower of London, which had a large store of gunpowder. The garrison at the Tower decided to take matters into their own hands, blowing up houses on a large scale around them, halting the advance of the fire and protecting the Tower.

As St Paul’s Cathedral was a brick building, many assumed it was a safe refuge and had filled it with possessions. The booksellers and printers around Paternoster Row filled the crypt with their books and other papers, however, the building was undergoing repairs and it wasn’t long before the wooden scaffold caught fire. Within half an hour of the fire taking hold, the roof had melted and everything in the building was up in flames, the cathedral was in ruins before the day’s end.

Wednesday, 5th September 1666

The winds began to drop in the early hours of the morning and the firebreaks created by the Tower of London garrison really started to take effect. Pepys climbed Barking Church and from the tower, took in the destroyed city, he noted in his diaries that there were still several separate fires burning around the area.

At this point, a large encampment had been set up in Moorfields on the outskirts of the city, where the newly homeless had congregated. Morale was low and violence continued in the streets as more and more people became convinced that the fire was an act of war. A huge explosion caused a mob to surge onto the streets, believing it to be the beginning of an invasion. The mob attacked any foreign people they happened to find and order had to be restored by soldiers.

Thursday, 6th September 1666

The final fires were extinguished on the Thursday, though some fires in the cellars of several buildings continued to burn for several months. The mood continued to be volatile and food production and distribution had been severely impacted, so Charles II ordered for bread to be brought in and for a series of markets to be set up around the perimeter of the fire zone.

By the Saturday, the senior governance of the City of London, known as the Court of Aldermen, began to clear the debris and reestablish supply lines. At this point, the markets were operating well enough to supply all the newly homeless living in camps around the City and Charles made a Royal Proclamation, imploring surrounding towns and cities to take in those that had been displaced. He actively encouraged those who had lost their homes to move away and start fresh.

Another proclamation was released which forbid people from speculating about the cause of the fire, though this did little to quell the rising violence against Dutch and French nationals.

Image: A map of the where the fire spread

The aftermath

With the Anglo Dutch War continuing in the background and violence against all foreign born people around England, a scapegoat was needed to quell the unrest in the streets. Robert Hubert, a French watchmaker made a confession that he and his gang had started the fire in Westminster and then, when it was pointed out that the fire didn’t reach Westminster, he instead said that he had thrown a grenade through the windows of the Bakery on Pudding Lane. He had clearly never been there, as his description of the building and its windows was incorrect. He was known to have mental health issues and poor mobility, so much so that it was deemed impossible for him to have thrown a grenade.

Despite this, he was French, so was a suitable candidate for blame. Thomas Farriner in particular was under pressure to prove that he had properly extinguished his ovens and he and his family all signed the Bill of Execution. Hubert was sentenced at the Old Bailey and executed at Tyburn on 27th October 1666. As his body was being handed to the Company of Barber Surgeons for dissection, he was torn apart by the assembled crowd of angry Londoners.

Following his execution, it was discovered that Hubert wasn’t even in London when the fire started, he was on a boat in the North Sea and didn’t arrive in the city until after the fire was already ablaze. His death did however stop the violence.

According to official records, only 6 people died in the fire. However, the records only accounted for those who died of burns or smoke inhalation. Very little is known about the undocumented poor, those who may have died in the impromptu camps or during the violence that followed. Many deaths likely went unreported, and certainly those who survived but had long lasting health issues were not counted. It is also worth noting that the fire was hot enough that there would have been little evidence left of anyone caught in the blaze.

Apart from the loss of life, the fire destroyed 13,500 homes, 87 churches, 44 company halls, The Royal Exchange, Custom House, St Paul’s Cathedral, Bridewell Palace, a number of other prisons, the General Letter Office, Baynard’s Castle and three of the city gates. The total cost of the destruction totalled to around £10 million, which is several billion in today’s money.

In the months after the fire, a committee was set up to establish the cause, which for a time, concluded that Hubert was part of a Catholic plot. It has since been established that even if the Farriners had properly extinguished the ovens, it would have only taken a spark to light up the wooden homes.

To avoid delays with planning and land ownership, a special Fire Court was set up in February 1667 and ran for several years dealing with disputes and deciding what should be rebuilt and where depending on the landowners’ ability to pay. Cases were dealt with swiftly, often in the same day, and helped with the speedy reconstruction of the City. Despite this, it still took around 50 years for the area to be completely rebuilt. Sir Christopher Wren was one of the many people who proposed plans for rebuilding, his plans were rejected, something that many have disagreed with in the years since. His plans would have made the City of London rival Paris. Instead, likely for speed and financial reasons, the City was rebuilt along the same street plan as before, however the reconstruction saw improvements to hygiene and fire safety, with buildings being remade with brick and stone. Most private rebuilding was completed by 1671, and new public buildings were created on their former sites, including St Paul’s Cathedrals and 51 new churches designed by Christopher Wren.

In 1667, strict fire regulations were imposed to reduce the risk of anything like this happening again. Nicholas Barbon, an economist, created the first insurance company, Nicholas Barbon’s Fire Office, which gave cheaper rates to those in brick buildings and hiring private firemen. Confusion between Parish and private firefighters eventually led to the newly emerged insurance companies creating a combined firefighting unit, which would go on to become the London Fire Brigade. Another fun fact about Barbon, he was one of the many who proposed rebuilding plans and is credited with shaping London as we know it today – despite regulations making his development illegal, he built up the Strand, St Giles, Bloomsbury and Holborn.

The fire disrupted commercial activity, with stock and premises being destroyed along with homes. Economic recovery was slow, however, London retained its economic pre-eminence and its central role in political and cultural life. The fire also continued to be used a as a political issue throughout Charles’ reign, especially during the Exclusion Crisis, as allegations that the fire was a Catholic plot were used as propaganda.

For visitors today, the most obvious reminder of the fire is the Monument to the Great Fire of London, which is located outside of Monument tube station. It was commissioned by King Charles II and designed by Sir Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke close to where the fire originated on Pudding Lane. It is 202 feet tall, the site of the bakery is 202 feet from the site of the monument. It took 6 years to complete.

.jpg)

Image: The Monument to the Great Fire of London

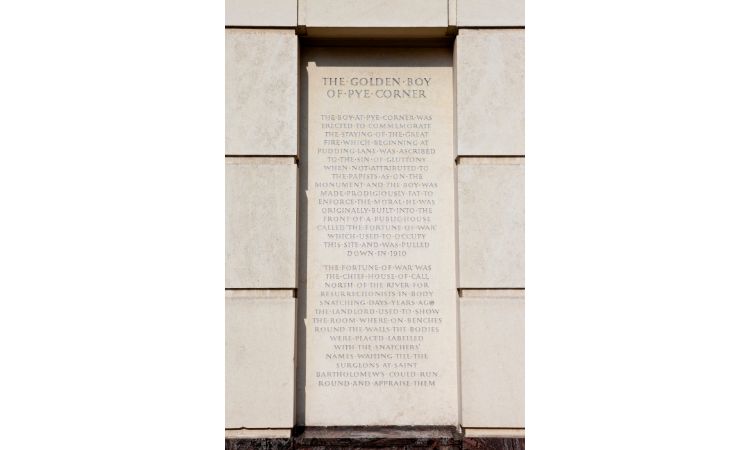

In 1681, accusations against the Catholics were added to the inscription on the Monument, something that remained until 1830. There is also a monument at the spot where the fire is said to have died out – the Golden Boy of Pye Corner in Smithfield.

The Monument to the Great Fire of London is a tourist attraction and is open daily for tours. There are 311 steps to the top where you can enjoy breathtaking 360 degree views of the City.

.jpg)

Image: The plaque at the Monument

Reactions around the world

As England was at war when the fire broke out, several nations did consider the fire to be retribution for events that took place during the war. The King of France, the nephew of the Queen of England, put aside their differences to offer aid and food to Londoners in need.

Image: The plaque at the Golden Boy of Pye Corner in Smithfield

So, there you go, a not so brief look at the circumstances surrounding the Great Fire of London. As well as changing the City physically, the Great Fire had a significant impact on the political, social, economic and cultural element of the capital and caused the largest dislocation of its residential structure in history, something only rivalled by the Blitz in WWII.

Related

Comments

Comments are disabled for this post.

.png)

to add an item to your Itinerary basket.

to add an item to your Itinerary basket.